Rules and exceptions

A large portion of our behaviour is guided by rules (some made for us, others made by us) … but it is exceptions that truly can help us understand others – and verify whether our own are up to scratch

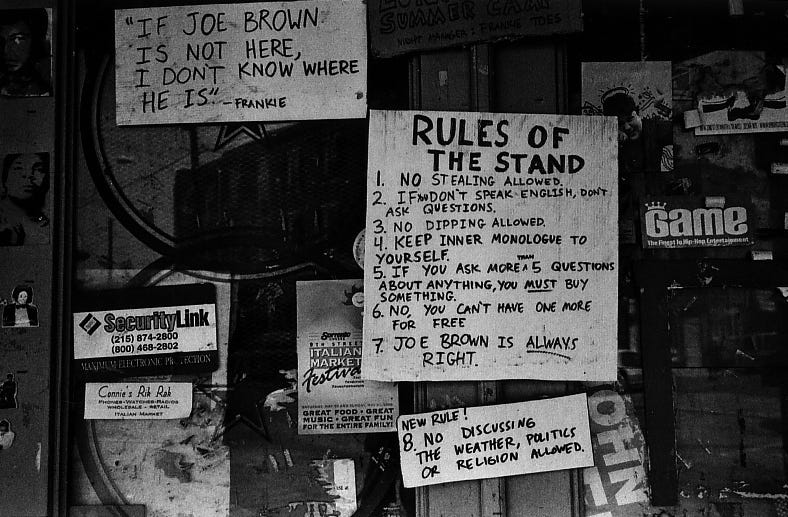

Whether you are a native speaker or not, you will have noticed that English orthography is, well, idiosyncratic. You may have come across ghoti as an alternative way to render what sounds like ‘fish’, or maybe even seen ‘potato’ spelled as ghoughpteighbteau. Yet, surprisingly, English does have rules of orthography – a popular (yet frequently broken) rule of thumb is “i before e, except after c”. We write field and tier, but receive and ceiling. Perhaps even more surprising is that this model – pairing a general rule with an exception – is deeply ingrained in our own cognition. A shop may be closed on Mondays, except on Bank Holidays, or car parking may be restricted, except for vehicles displaying a permit. However, ubiquitous as rules and exceptions are, their use is not without pitfalls.

Rules rule our world…

Simple rules are invaluable as cognitive shortcuts which, based on scant information, predict what is likely to be the case, and indicate the best course of action. Our most distant ancestors regularly faced situations that could mean their untimely death, or a failure to pass on their genes. When evolution eventually led to an emerging ability to detect and distinguish beneficial from detrimental situations, those organisms that possessed it had the edge over their less fortunate relatives… and millions of generations later, we are still benefiting from a – now much more refined – ability to model and predict the world around us, all thanks to rules.

For a long time, their value was exclusively in how they guided individual organisms through their environment helping them stay alive, reproduce and flourish. Yet as some organisms began to form groups, cooperating and relying on each other, things became more complicated, and two issues arose. Predicting fellow group members’ behaviour turned out much harder than predicting nature: people are too capricious to allow their behaviour to be described in simple, useful rules. Furthermore, in order to coordinate cooperation, and handle interpersonal interaction, prescriptive rules were needed that surpassed individual interests, reflected the interest of the group, and were consistently followed by group members. Of course, as all these rules became more complex and specific, they sometimes came into conflict with each other, and people and groups alike needed to establish hierarchies to settle on which rule took precedence in which situations: should we “stay with the group for safety” or “go hunting to provide food”?

Fast forward to today, and rules still very much rule our world. Many of the choices we make every day, we make efficiently and quickly thanks to them: we stop at red traffic lights without thinking about it, we automatically join queues when waiting or hold doors, we don’t even contemplate pinching items from the store (even though we easily could), and when we have a problem, we ask someone who knows better than we do.

Sometimes, however, rules that usually function excellently don’t quite seem to fit. Just like the spelling rule, they cannot possibly address all possible eventualities, so we use a complementary mechanism to handle this: the exception. We effectively reserve the right to declare a rule inapplicable in certain exceptional circumstances – much more elegant and efficient than adjusting rules or reintroducing new ones, and reshuffling the hierarchy. We may have a rule to clean our teeth before going to bed, but when we come home in the small hours, tired and perhaps a little inebriated, we invoke an exception and skip the teeth brushing. Similarly, many people appear to consider that engaging their car’s hazard lights affords them an exception any prevailing rules that restrict parking.

…but exceptions rule the rules

But this powerful rules-and-exceptions mechanism also has its downsides. The rules we make up ourselves don’t have the benefit of countless generations of evolutionary fine tuning. Some may be based on ideology instead of facts (“local produce has a lower carbon footprint”), faulty intuitions (“international trade is a zero-sum affair – don’t be at the losing end”), conspiracy theories (“avoid vaccines”), or incompetent reasoning (“thousands of bitcoin investors cannot be wrong”). And rules, even the suspect ones, tend to continue influencing us.

Also, our rules are rarely as clear-cut as the spelling rule – many are vague and rest on unspoken assumptions. Almost everyone would happily sign up to a rule stating “be loyal to your relatives and friends”, but what exactly this means in detail is neither documented nor universally shared. Aside from those enshrined in law, societal rules that help us manage interpersonal interaction are often implicit, ambiguous and difficult to enforce. When it then comes to conflicts between rules, the much deeper roots of simple, self-serving rules – originally concerned with ensuring survival and reproduction, and shaped over hundreds of millions of years of evolution – mean our individual interest often prevails over the group interest. This pursuit of one’s own interest to the detriment of that of others, seen through the lens of conflicting sets of rules, explains not only rifts between relatives and (potentially former) friends and acquaintances, but also fights, crime and war.

Unfortunately, exceptions are the perfect instrument to deal with rule conflicts in a self-serving manner (“Speed limits must be adhered, except when I am running late”). Together with motivated reasoning they can justify any refusal to comply with a societal rule, or to respect another individual's rule. Self-serving impulses can be suppressed through concern about our reputation: even though we might be able to steal for our own gain from someone who trusts us, the risk of losing our reputation if we are caught (or indeed our own moral sense of right and wrong) will prevent us from doing so. (Naturally that only applies to people who actually care about their reputation.)

The greatest danger, however, is that exceptions morph into full-blown exceptionalism – the belief that one is inherently entitled arbitrarily to invoke exceptions that others cannot. This transition from occasional flexibility to claiming systematic special treatment undermines the very foundation of rules. What begins as 'just this once' becomes a pattern, and eventually invoking exceptions becomes the new rule, customized to fit one’s own desires, emotions, and grievances rather than societal harmony and flourishing.

Rules serve not just to predict the world, but also to override harmful impulses (to us, and to others). They provide the scaffolding for social cooperation by making behaviour predictable and aligning individual interests with collective ones. Excessive exceptions weaken this scaffolding, and erode social trust with it.

Ultimately, it is not the rules people claim to uphold that tell us about their character, but the exceptions they invoke to those rules. People who champion fairness except when it disadvantages them, who value honesty except when lying serves their interests, or who demand accountability except for themselves, show us who they truly are.

Predicting other people’s behaviour remains a challenge. However, by noting not just the rules people proclaim but also the exceptions they permit themselves, we gain the clearest insight into their values, and the most reliable predictor of their future behaviour – for those in our immediate circle, and those acting on the national or global stage alike.

I am sure you can think of examples.