Are agriculture and nature poles apart?

The trickiest of decisions are those where "either/or" is out of the question.

The farmers’ protests in Belgium have been continuing unabated this past week, though an agreement was reached this morning. One of their grievances is their feeling that their interests come a distant second to the protection of the natural environment in government policy, which includes the purchase of agricultural land to turn it into conservation areas. In a radio news bulletin Tuesday morning, correspondent Sanne Baeck reported that farmers blamed the politicians for “polarizing between agriculture and nature” – an interesting turn of phrase, describing the situation perhaps more precisely than might first appear.

The term ‘polarization’ has been gaining currency recently, as it captures the growing erosion of political compromise on a wide range of issues, the relentless emphasis on ideological divides (often with limited ties to the political families’ traditional values) and, ultimately, identity politics. This trend is particularly apparent in nations where political life is dominated by two parties, which have evolved into polar opposites. But such polar opposites arise everywhere, not only in party politics.

Many of the choices we face involve making a trade-off. Whenever a scarce resource can be spent on different purposes, we must decide how much of it should go to each one. A bit more to one purpose means a little less to another: if we want to spend more money on eating out, we must cut down on going to the cinema, for example, or if we want more leisure time, we can opt for working part-time (and earn less money). In other cases, we must make a choice between two mutually exclusive options, both of which have advantages and disadvantages. If we have whittled down the suitable possibilities for renting a flat or a house, one may be close to public transport connections, but on a busy thoroughfare; the other is in a quiet cul-de-sac, but means a brisk walk to the station. We then need to ponder what we like (or dislike) most: tranquillity or connectivity (or brisk walks in all weather, or traffic noise all day and until well into the night).

Poles apart

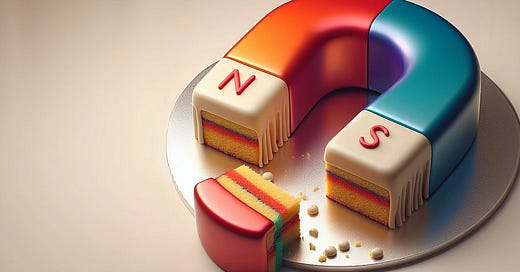

But there is a third category of decisions we may need to make, where both options are (de facto) polar opposites, and yet we need both of them. These are called polarities. Usually, they relate to how we handle broad goals, values or aspirations. For example, we need stability in our lives, but we also need change; we want to express, and live according to, our individuality, but we also want to belong. (You might even say that sometimes we want to have our cake, and we also want eat it.)

Such polarities are sometimes called wicked problems, paradoxes, or dilemmas, which illustrates their challenging nature. They can neither be resolved by working out a trade-off between the two poles, because there is no exchange rate we can try to discover. They are also not independent, but interdependent: you cannot choose one as the solution, and ignore the other. It’s not either/or, but both/and. So, the protesting farmers may not have been fully familiar with this somewhat obscure concept from decision science, but they pinpointed a wicked problem the Belgian governments (yes, there are several, just to complicate matters) face. Agriculture and nature are both important, and having to manage them simultaneously is a polarity.

And that can be quite a challenge. To understand why and how, a metaphor might help: our body needs oxygen, so we need to inhale, and it must expel carbon dioxide, so we need to exhale. Imagine we had to consciously decide exactly when to breathe in or out at any one time – we would then face a genuine polarity. The first issue is that we fail to spot this, and try to solve for an optimum balance between breathing in and breathing out, setting our respiration rate based on the current requirement for oxygen and amount of CO2 in our body that needs to be released. However, as soon something changes in our circumstances, our need for oxygen will go up or down, and the chosen respiration rate is no longer appropriate. We face a dynamic challenge, and that cannot be handled with a static solution. The second problem is that our attention goes to just one of the poles. Imagine you are singing, and your only concern is to produce enough breath to sing a really long phrase, something like Bill Withers singing Ain’t no Sunshine (from about 0:52), or Focus’ Thijs van Leer yodeling in Hocus Pocus (from about 4:02). Thankfully, singers (and the rest of us) can rely on our autonomic nervous system to handle breathing, and step in to manage the polarity if we mess with it. Without it, we might be seeing singers like these two gentlemen drop dead with alarming regularity.

Polar trouble? Polarity thinking!

Policy making faces similar challenges. If the tension between the needs of the farmers and of nature preservation is not seen as a polarity but as an ordinary problem to be solved, ministers might instruct data analysists to come up with policy proposals. These would undoubtedly be fine proposals, with a perfect fit for last year’s requirements, but today, sadly, completely out of date.

An even more infuriating problem would be, as is often the case, that whoever or whatever makes the most noise becomes the focus of attention. Ministers might favour their electoral supporters, or the most effective lobbyists for vested interests, and consider the corresponding goal as the only one that counts. That approach may appear to work for some time… until the tension between it and the other pole erupts. It is easy to see how, if policy focus has long been almost exclusively on environmental goals, driven by public opinion, activists and perhaps even ideological agendas, the interests of an important, but diminutive group – the farmers – tends to be neglected.

A better way to handle polarities was developed by organizational psychologist Barry Johnson. It recognizes that – bearing in mind F. Scott Fitzgerald’s words, “The test of first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function” – the two opposing goals must be simultaneously and equally considered. The key is seeing that too much focus on goal A (nature preservation) might threaten goal B (the interests of the farmers). When choices are made related to meeting goal A – this could be minor adjustments, or large interventions – priority should be given to those options that serve both goals, or that do not hamper goal B. If that is not possible and the other goal risks being compromised, then mitigating action should be taken. The cycle then continues with taking steps to support goal B, and conversely addressing any threats they pose to goal A, closing the continuous loop.

Modern organizations are also rife with polarities: centralization and decentralization, cost reduction and quality improvement, loyalty and contrariness. These are no less challenging than those in government. Naturally, no organization wants its staff to be disloyal, but too much emphasis on loyalty risks leading to conformity and groupthink. Dissent that challenges the status quo is essential for innovation and improvement, but not to the point of anarchy. Working out the perfect dosage of either makes no sense at all, and focusing on one until the other becomes untenable is not the right approach either. It is better to recognize the tension as a polarity, which can then be managed accordingly, with a constant eye on cultivating both loyalty and contrariness in the behaviour of the employees, and continually navigating the upsides and threats related to each of the two goals.

And in your own, private life? Do you want to sleep more and go to bed later (or get up earlier)? Would you like to make a good impression at work by putting in the hours and have more leisure time? Do you think it would be nice to do things with the family, and have some me-time as well? Maybe there, too, some polarity thinking could help.