Can price controls beat the market?

Economists have been insisting that price controls are bad economics forever. Are they (unconditionally) right?

People not only prefer lower prices to higher ones, but also often instinctively assume that higher prices are indicative of profiteering. Common wisdom would seem to have it that a price should be, if not equal to the costs, then at least very close to it. So, when prices rise, especially when they do so rapidly, the suspicion of profiteering strengthens. That is when citizens look to the government to put a stop to ‘price gouging’ and ‘greedflation’: they want it to prevent retailers or landlords from increasing prices. It is then tempting for politicians to heed those calls and introduce price controls.

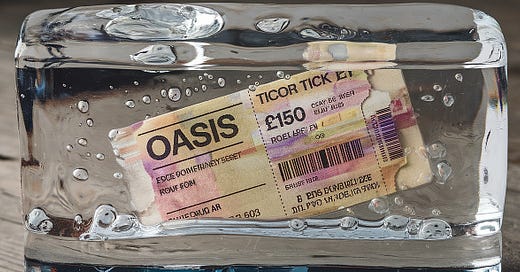

A recent high-profile instance is that of tickets for the reunion tour of the rock band Oasis. These carry a face value of around £150 (€175) in the UK for the most popular ones. That may seem expensive, but with a hard limit on the number of tickets, and huge demand, it was no surprise that within hours, tickets were offered on reseller sites at up to 40 times face value. This was despite the fact that the band had stated that tickets could only be resold at face value through official resellers (and that other tickets would be cancelled) – a de facto price control measure.

Prices as a lubricant

Most economists dolefully shake their heads at the idea of price controls. Prices are the lubricant in a market, ensuring that the available quantity of a good or a service and the quantity demanded remain in equilibrium. They are, in a sense, the ultimate behavioural economics instrument. They directly influence the behaviour of suppliers and consumers, through their own behaviour. If goods become scarcer, because either supply falls or demand rises, consumers who really need them will offer a higher price. This pushes the market price up, sending a signal to the consumers to consume less, and to the suppliers to produce more. The ensuing change in behaviour nudges supply and demand in the market towards a new equilibrium. Similarly, when goods become more abundant (through excess supply or a reduction in demand), suppliers will cut prices to ensure the excess gets sold, sending a signal to reduce production, and at the same time encouraging consumers to increase consumption.

This is the case for a wide range of goods and services, from groceries, fuel, haircuts and cinema visits to building materials, rental properties, and holidays. Introducing price controls, economists argue, eliminates the key signal that informs players to alter their behaviour and help remedy scarcity. The consequences are well known: hoarding, empty shelves, and persistent shortages.

But wait. Does this apply to Oasis tickets, too? Arguably, market-priced tickets might significantly cut demand from the 14 million that reportedly tried to buy one of the approximately 1.4 million tickets available – although certainly not by 90%. At the supply side, the constraints are clear – Oasis’ capacity to supply concerts is obviously limited. A few more gigs, sure, but ten times more is just not possible. If the price signal would, so to speak, fall in deaf ears, does the economists’ objection to price controls still hold?

They might argue that it does. Fixed prices lead to inefficient allocation, since available goods are not going to the buyers who value it the highest, i.e., with the highest willingness to pay. The exact same item may indeed represent different values to different people. Consider an auction where multiple bidders compete for an item. The auction ensures that it goes to the highest bidder, the person who values it the most. This maximizes economic value because the seller receives the highest possible price, and it delivers the highest value to the buyer. If the item were sold to someone other than the highest bidder, the economic value would decrease. The seller would receive less money, and the buyer would value the item less than the highest bidder would have. This difference represents the lost economic value due to inefficient allocation. In this respect, the band’s stated policy prevents more efficient allocation. People who value a ticket more than face value cannot buy it for a higher amount from current owners prepared to sell it at this higher price. This leaves both parties worse off.

However, there is another perspective worth acknowledging. Through their choice for a binding, low ticket price, the band sends a costly signal to its fans, as it could clearly have made more money by charging more. This choice may well pay off materially in the long run (by boosting loyalty, which will eventually be translated in higher sales of music and other Oasis-related items). Even if it does not lead to more money for the band, it will enhance its reputation, and who knows, this might have value for the Gallagher brothers in its own right.

As it happens, the situation is further complicated by the fact that Oasis does not have full control over the ticket sales. Promotors, who pay the band an agreed fee to appear, and ticket sales agents retain some autonomy on price setting, notably through the booking fee, or “in demand” surcharges. This increased to total selling price by no less than £200 during a certain period, before it was cut to £25 under (social) media pressure. While the band was quick to state they knew nothing of this arrangement, it may well have taken some of the shine off their reputation-enhancing ethical stance…

Market forces prevail

Economists are certainly on to something if they say that a market with free competition is a better way to ensure low prices than price controls. However, lack of competition (there is only one Oasis), and supply constraints mean that there is no downward pressure on the price. Yet even in this unusual situation, we can see that controlling prices is not without its difficulties.

A key reason is that a market is not quite a theoretical economic construct. It is a manifestation of a range of human behavioural tendencies. Evolution has shaped us to be frugal with our resources, and so, while we seek maximum value in what we purchase, we also seek to pay the lowest possible price. As buyers, we are bargain hunters, who tend to view the portion of the price over and above the cost to produce the good or service – i.e., the gross margin – as excessive.

On the other hand, however reluctantly, as buyers we are also prepared to pay more to secure the object of our desire, up to the actual value we perceive. We can see this in the fact that numerous buyers paid the inflated “in demand” ticket fees, suggesting that their willingness to pay was well over twice the face value.

Moreover, as sellers of unwanted tickets, we are not afraid to ask for amounts well above face value. Viagogo, a secondary ticket reseller site (which insists offering Oasis tickets for resale is entirely legal) currently lists standard tickets offered at prices between about £550 and more than £3,000. We may well demand price controls when we are buying tickets, but we are clearly not so keen to control prices when we are selling them, quite happy to demand whatever the market is willing to offer.

Whether it concerns concert tickets, housing, groceries, or pretty much any other product or service, the basic economic laws of markets cannot be escaped. Governments can freeze prices, but they cannot force producers to supply more, nor prevent buyers from offering a higher price if a product is scarce – if necessary on the black market. British prime minister Sir Keir Starmer promised the government would “make sure that actually, tickets are available at a price that people can actually afford." He is not an economist, but even a lawyer should realize that the underlying scarcity of a good, which leads to price rises, cannot be resolved by freezing its price. The choice consumers face is between a product that is scarce, but available at a higher price, and a product that is ‘affordable’, but unavailable.

To paraphrase the title of Oasis’ debut album, there is no maybe about it: price controls can definitely not beat the market. Because the market, that is us.

For markets to function properly, it is essential that both buyers and sellers have bargaining power, and economists routinely forget to mention this prerequisite. Most importantly, it is vital that both parties can reasonably choose to stay out of the market. For Oasis tickets, this is mostly the case because you can always elect not to go if you think tickets are too expensive. For so many other ‘markets’, however, this is not the case. In housing, health care, and to some extent energy and groceries, it is simply not an option to stay out of the market completely. Therefore in these markets, ‘efficient allocation’ using prices can deviate a lot from ‘fair allocation’, and so there is a role for governments to intervene when necessary. The basic assumptions for markets are simply not met.